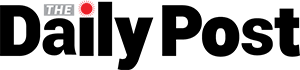

Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital and one of the world’s most densely populated cities, has earned the nickname ‘rickshaw capital of the world’. The city is home to an estimated one million cycle rickshaws. And in only a few short hours in Dhaka, you’ll feel as though you’ve seen that many.Colored brighter than a rainbow, the rickshaws are impossible to ignore on the city’s chaotic streets. But it’s the illustrated tin rectangles at the back of the rickshaws that catch my eye first, leading me to seek out some of the artists.Cycle rickshaws have been plying the streets of Bangladesh since the 1940s, but illustrations only started to adorn them in the 1950s. And it was during Bangladesh’s struggle for independence from Pakistan in the early 1970s that rickshaw art bloomed.

The period of transition and violence leading to independence in 1971 saw rickshaw art take on a more political and propagandist tone, with illustrations of Bangladeshi moon landings and Pakistani war atrocities.Rickshaw art continues to capture snapshots of Bangladeshi life, providing a space on which to express something about popular culture, beliefs and aspirations. Depending where in the country you visit, the art changes. In Dhaka, pink-hued movie stars’ faces and depictions of the Taj Mahal are popular; in the northeastern city of Sylhet, illustrations reflect a devotion to Islam while in Khulna, in the southwest, depictions of trains and planes are fashionable.

And the point of all this colorful eye-candy? It was, and still is, to attract customers to hire the rickshaw. Good old-fashioned marketing. It’s not as simple as keeping with tradition. Traffic congestion is a problem across Bangladesh—getting from one side of Dhaka to the other can take hours and for the government, rickshaws are a symbol of underdevelopment and the scourge of congestion in the country’s crowded cities. And yet, with one in four Bangladeshis living in poverty, rickshaws remain an essential and affordable mode of transport.

Bonjo trained as a rickshaw artist in 1969 and has had his own workshop for 35 years. Three students trained under him, but none work as rickshaw artists any more, “There’s not enough work for them now. A few artists I know left Bangladesh to work in the Middle East,” he says. A few days later, in the northeastern tea-growing town of Srimangal, I meet local artist Bulbul in his studio. Opposite the door is a wall mural depicting victims of the famine that ravaged Bangladesh in 1974.

Bulbul no longer paints rickshaws. “I stopped about 14 years ago, I’m a sign-painter now.” He opens a book, demonstrating how he checks the spelling for the signs he paints. “Mass-produced artwork is to blame for no-one wanting hand-painted art. We can’t compete with the price,” he adds. Back in Old Dhaka, where this colorful odyssey began, I meet Yousuf again. The narrow, leafy courtyard of his apartment, where neighbors chat and children play, is also his home studio while the corner opposite his front door serves as his compact workspace. An easel, paints, brushes and canvases are organized on a wooden platform at which Yousuf sits cross-legged.

“My father was an artist and I learned how to paint from him,” he tells me. “My six brothers are all artists too.” Yousuf’s father is a renowned first-generation artist called Golam Nabi. Acceptance and adapting seem to be key to survival here for Bangladesh’s talented rickshaw artists. While Yousuf’s first love is painting rickshaws, he also enjoys painting vibrant wildlife scenes and depictions of idyllic village life. “The artwork for tourists is more varied than the work I create for the rickshaws,” he says. It’s also more sophisticated and detailed than the work I’ve seen on the rickshaws, I note.

With the push to remove rickshaws from the roads and the rise in mass production and digitization, it’s hard to know how much longer Yousuf and those like him will be able to continue their work.

Still, Yousuf himself is hoping to pass down his skills. In fact, his young daughter, Asha, is sat beside him, watching her father paint and playing with his brushes. “She seems interested in learning to paint,” he says, looking down at her—with something that looks a lot like pride.

“No, I’m too old,” he smiles. “I’ll stay, even though there’s less work.”

When work does come in, Bonjo works around the clock, alongside his son, who is not an artist. The pair is finishing a bulk job of 10 new rickshaws, which they’re painting with simple water-lily motifs, the national flower of Bangladesh. In the workshop next door, three lively young men stitch rickshaw hoods and seat covers with lightning speed. Stacks of embellished plastic panels line the shelves and the floor space is cluttered with bags of trimmings and rickshaw parts. It’s the combined effect of the artwork and appliqué decorations that make Bangladeshi rickshaws the most striking and unique I’ve ever seen.

Recently Bangladeshi rickshaws and rickshaw paintings were added to Unesco's list of the world's "intangible cultural heritage of humanity". The honor was bestowed during the 18th meeting of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, which is now taking place in Kassanne, Botswana. "The rickshaw is a human-propelled transport on three wheels and is a recognised feature of Dhaka and Bangladesh, as a whole. Rickshaw craftsmanship has been highly renowned for its traditional process of fashioning it by hand. In Bangladesh, almost every part of a Rickshaw is decorated and painted," Unesco said in a statement. "Rickshaws and rickshaw painting are viewed as a key part of the city's

cultural tradition and a dynamic form of urban folk art, providing inhabitants with a sense of shared identity and continuity," it added. Apart from rickshaws and Rickshaw paintings, some of the new inscriptions include India's Gujarat's 'garba' dance, Songkran, the traditional Thai New Year festival, hiragasy, a performing art of the Central Highlands of Madagascar, Junkanoo from the Bahamas, among others. Unesco's list of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity has some 704 elements corresponding to 5 regions and 143 countries. It includes forms of expression that testify to the diversity of intangible heritage and raise awareness of its importance. By enhancing the viability of communities' cultural practices and know-how, Unesco aims to safeguard the intangible cultural heritage of communities globally.

"Rickshaws and rickshaw paintings" is Bangladesh's fifth entry in the list. The entries are Jamdani and Shital Pati weaving industries, baul songs and Mongol Shobhajatra.

ARS